Rice Coral

Rice coral – named for the rice grain-sized projections on the skeleton surface – is one of the four most common corals in Hawaiʻi. It can be dominant in quiet-water habitats: typically occurring on lower reef slopes, below the effects of the wave surge and down to depths of 150 feet (45 m); as well as the shallows of protected bays, like Kāneʻohe Bay.

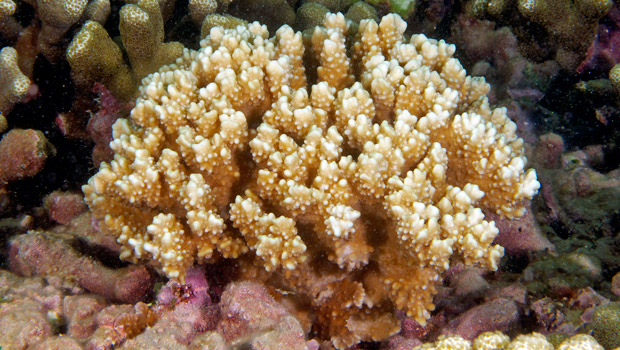

Rice coral assumes a bewildering variety of growth forms, depending upon the reef environment in which it is found. Sunlit colonies can grow into fragile, spiked pinnacles, while colonies that are shaded or in deeper water grow as bracket-like plates, fanning out to gather available light. Both growth forms can even occur within a single colony, where upper branches shade the lower ones! Rice coral colonies also vary in color, from dark chocolate brown with whiter branch tips to a more uniform cream-color. This variation of form and color led to early confusion about its scientific identification.

The individual coral organisms, called polyps, are simple vase-shaped creatures. Each has a central mouth, surrounded by a ring of tentacles. Rice coral colonies consist of thousands of polyps, all descendants of one original founding individual. The polyps of a colony are connected to one another by both their skin-like layer and simple gut cavity. The living tissue of the coral is only about 0.4 inches (1 mm) thick, yet it produces a hard limestone skeleton that contributes much larger structures to the reef.

One of the keys to coral growth lies in the special partnership that corals have with microscopic algae, called zooxanthellae, which live within their tissues in a symbiotic relationship. Using sunlight and nutrients from the water and their coral hosts, zooxanthellae generate energy-rich compounds through photosynthesis. These carbon-rich products are important in the energy budget of rice coral. Additionally, rice coral appears to gather some food particles by suspension feeding, collecting particles of organic matter that drift down from above.

Rice coral is featured in Aquarium exhibits depicting quiet-water reefs, both at the outdoor Edge of the Reef exhibit and in the Hawaiian Marine Communities Gallery exhibit on Kāneʻohe Bay. Colonies in the Edge of the Reef exhibit spawn on a precise schedule – two to four nights after the new moon in June and July – just like their relatives in the wild.

Quick Facts

Hawaiian name

ko’a

Scientific name

Montipora capitata (formerly identified as M. verrucosa)

Distribution

Indo-Pacific, including Hawai’i

Size

variable, polyps 0.04 inches (1 mm) in diameter, colonies to several feet (m) across

Diet

nutrients produced by symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae) & organic particles collected by suspension feeding

Support the Aquarium

Contact Us

Honolulu, HI 96815

(808) 923-9741

Search

- Already a Volunteer?

- Click Here To Sign In

Donate

Donate